11 Jun The Sixth Cot from the Window

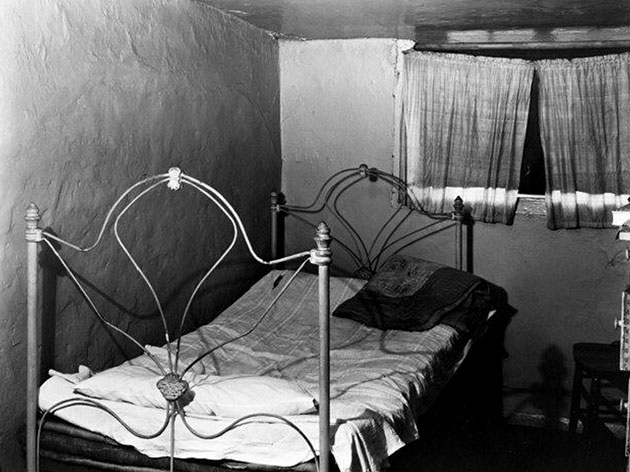

Jim’s Boarding House used to cater to railroad workers who had to layover in Madison. When railroads became less popular and trucks began to ply the highways of Wisconsin, Jim’s clientele turned from railroad workers to tramps, hobos, drunks, and transients. Jim’s Boarding House was a two-story building with separate rooms upstairs and a large dormitory kitchen, dining room, and parlor downstairs. It became more of a “flop house” than anything else and it was on my paper route.

I had four customers at Jim’s; the sixth cot from the window and three upstairs rooms. I delivered the papers to the upstairs room first because it was spooky up there and it gave me the willies. The hallway was dark and dirty and always littered with trash bags and beer bottles.

My customer in the row of cots was an old, old man. His hair was white and yellow as was his long beard. He always wore bib overalls and you could see the outline of a snuff box in the upper pocket. A streak of tobacco stain colored one corner of his mouth and flowed into his beard. He was tall with watery blue eyes and his fingernails were long, cracked, and yellow. I once saw his feet and I wished I hadn’t. His toenails were long and curved. I wondered how he got his shoes on and then I realized he only wore slippers. I don’t think he ever left the building.

I was afraid of him until I saw his eagerness for the Capitol Times. He sat on his cot and pulled his night table over to him and spread out the paper. He had to work at reading. His glasses had only one ear piece and he had to hold them on with one hand as his lips moved to every word. It was the high point of his day and it made me feel good that I could provide it for him.

Every Friday, I collected for the weekly paper. I knocked on the doors upstairs and said, “collect for the Capitol Times.” Sometimes I could hear someone stirring in the room, but they wouldn’t open the door. If I hadn’t collected for two weeks, I would see Jim and he would open the door and shake seventy cents out of the tenant. After that they usually paid every week.

The old man on the sixth cot from the window paid weekly and he made it seem like a big business transaction. He took out his change purse and opened the clasp. He counted out thirty-five cents with great care and gave me his Capitol Times card. I made a hole with my punch, obliterating the appropriate week. “Paid for another week,” he would say.

He put the card back in its place in the night stand drawer and pulled out a yellowed newspaper clipping and handed it to me. There was a picture of a man on his knees laying paving bricks. In the picture the man was placing one brick with his right hand while reaching back with his left for another supplied by a helper. The article said the man in the picture was Walter Kuehn, the world’s fastest brick pavement layer. It went on to tell how many bricks Walter had put down in a nine-hour day, stopping only for a short lunch and water breaks.

I looked at Walter and he half-grinned back at me. It seemed impossible that the man in the picture and they one standing in front of me were one and the same. He took the newspaper article and carefully put it back in his night stand.

“See you Monday,” he said.

I said, “See you Monday, Mr. Kuehn.”

The next Friday, collection day, I took my last breath of fresh air and entered Jim’s Boarding House. The smell was an almost overpowering mixture of tobacco smoke, unwashed men, and half-full spittoons. The fried onions and greasy hamburgers that seemed to be the daily fare added to the miasma to make it stick to your nostrils for an hour after you left the place. I went upstairs and collected from the men in the private rooms, giving them their papers and punching their cards. Creaking down the wooden stairs, I looked for Mr. Kuehn’s bunk, counting six from the window as I entered the dormitory area. The mattress on his cot had been rolled up, folded blankets and a pillow rested on the roll. I counted again to make sure, “five… six…” Still the same.

A derelict two cots toward the window looked up at me. “Where’s Mr. Kuehn?” I asked.

“Mr. Death came for him last night,” he said.

“Mr. Death?” I said.

“Yeah, about midnight.”

I didn’t know what to say. Even at twelve years old, death had not been a stranger to me, but this seemed so sudden. I knew Mr. Kuehn was old but he seemed fine yesterday. Tears started to well up in my eyes but I didn’t want the unkempt man to see them. I half-turned and blurted out, “did Mr. Death leave me my thirty-five cents?”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.